-

Nadine Khalil

“Thinking about motherhood seems to require looking in two different directions simultaneously: to the past, when I was daughter to a mother, and to the future, where I became a mother to my son… What if a mother’s absence or disappearance is the point of reference you turn to or fight against when you become a mother? And what of the experience of motherhood away from home, when you yourself are absent from your “motherland”? Does this make you freer when playing the role of mother, or does it leave you more lost than ever?”

Iman Mersal, How to Mend: Motherhood and its Ghosts, 2017

I begin with this quote by Mersal because so much of Aya Haidar’s work is about lost homes in relation to the being-in-place that motherhood entails — an embodied, caring and constant presence. I am not a mother, but from the loss of my own mother, I understand that being a mother never ends. A mother is still a mother after death. -

Connecting Threads

In her work, Haidar turns domestic practices into a visual archive of personal and political histories. An image of her grandmother weaving and repairing at home lingers, the cross-stitch carrying shared histories of displacement across Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. In Haidar’s attempt to resist the destruction of craft as another casualty of war, she moves away from cultural iconographies from the region. You will not find the familiar, abstract designs of tatreez which index particular villages or regions of Palestine. Nor will you find artisanal, floral motifs common in abayas worn by women in Lebanon, where Haidar is from.

“Embroidery is something I grew up with,” she explains. “It felt like a tool of resistance that projected women on an expressionist stage. My interactions with my grandmother were at home, where she would hem and repair over long sittings. I always wanted to bridge the gap between the beginnings of embroidery and where we are in this moment.”

Forging a language that is all her own, she weaves words or snapshots largely based on true accounts or experiences:

The recent, devastating image of a Gazan woman silently grieving her dead baby, a shrouded figure, in the ongoing Israeli war against Palestine (Final Goodbye, 2024).A father handing over his daughter for sex work in Jordan’s largest Syrian refugee camp (Zaatari Camp, 2024). -

The latter was part of Haidar’s experience as director of Al Madad, a charity organisation she ran for seven years until 2017, while still pursuing her art. Haidar’s community-driven interventions, often focused on migrant communities and domestic work, emerge through her creative practice — which always existed alongside it. “I don’t work in isolation,” she says, “All these experiences filter through.” Women’s stories build and fester in the artist’s body and psyche over time, before they are transmitted in a single frame.

Identity politics has become so marketable in the art industry, but it was not the case when Haidar was finishing her BFA at the Slade School of Fine Art. Her tutors thought the questions she was asking through her socially engaged practice were better answered in an applied Masters rather than a creative one. Although she immediately got picked up by Bischoff/Weiss gallery during her 2008 degree show, which gave her “that leap of faith”, she took the advice to apply for an MSc in NGOs and Development at LSE and got in. It remains a training that corresponds to a need to enable those who are overlooked.

“Refugees are spoken about like a homogenous, faceless group,” she notes. “But the women I work with become a part of me. The only thing I can do is tell their stories, say their names…”

And a layer is shed.

CHRONOLOGIES OF BIRTH

Haidar situates every encounter, when something shifts inside, according to the timeline of each of her four childbirths. In real time, she draws out the aforementioned mother’s grieving gesture in Final Goodbye. She says it reminds her of the way she would hold and rock her babies to sleep every night, one arm cradling the head.

The disjuncture between a murdered child being held for the last time and a satiated, safe baby is too close to bear. I think I understand when Haidar says, “Having kids is my biggest form of activism.” Perhaps it’s like fighting for the possibility of another world while it breaks you. Home-making is not separate from the work you do in the world, she seems to think, they intersect and fuel each other. Being a mother and an artist are inextricable.

This in turn reminds me of my sprawling conversation with Patti Smith in 2022. She recalls nursing her child when the news of the famine in Somalia reaches her. On TV, a baby dies of starvation in her emaciated mother’s arms, who unaware, hands her over to Audrey Hepburn, who, there as part of a UNICEF campaign, expresses utter shock and horror. And it is televised. Smith describes this moment as crossing another threshold of empathy.

-

-

Collective Bodies

“I would ask my mother how she survived the Lebanese civil war day-to-day. She said they would wear pots and pans on their heads to protect against shrapnel, stand in the pool, and sleep under the bed. My grandmother would stack the furniture because the broken glass from explosions kept getting into it.”

We laugh at these DIY tactics and the familiarity of the never-really-post civil war stories we both grew up with and also, how we can track a heritage of dispossession through our mothers. Haidar’s parents, like mine, finally decided to leave Beirut during the 1982 Israeli invasion. “I remember mum’s thesis, on the morality of war, was the only thing she took with her when she walked from the American University of Beirut to her parents in the Doha region, which was under shelling then… They left to visit my uncle who was studying in the UK and never returned after the airport was bombed,” Haidar recounts. We trace complicated movements: her mother marrying her dad in Jordan, moving with him to Saudi Arabia, giving birth to Haidar in the US, then her sister in Canada and relocating to London when Haidar was six. The lines of my family’s trajectories to Cyprus, the UK, Nigeria and back to Beirut form a parallel map in my brain, one positioned between exiles and births.

We talk about this deep longing for Beirut as the place where we grew up or came of age (me), a place of summer adventures (Aya), and the thrill of freedom and precarity that is Beirut (both). In an earlier body of work, Seamstress, (2011-ongoing), photographs on linen of scarred urbanscapes and collapsed buildings in Lebanon are patched up with colourful threads. This concept is expanded in the new Shattered series (2024) referencing Beirut’s August 2020 port explosion, where the same type of beautification, a softening of jagged edges, hints at a grimmer reality.

-

The Past Merges with the Present

In Haidar’s world of recreated objects, recent history keeps expanding. She shows me an image of a water jug constructed from the melted shards of glass in Beirut post-blast. A red curvy line, made of flexible repair putty, runs through it like clotting blood. It belonged to her friend Tamima at a time when people were gathering the city’s broken windows to make these traditional Levantine pitchers (briq in Arabic). “In its second life, Tamima’s briq was fractured,” Haidar says. “I wanted to reinforce the crack by highlighting the breaks as scars — as broken parts of the city.” It’s an affront against selective amnesia, she explains.

The present merges with the past.

The sound of three symphonies playing simultaneously (Mahler’s Der Titan, Haydn’s Militär and Beethoven’s Eroica) in Tabari Artspace captures the dissonance and turbulence of the past. It is music belonging to Haidar’s grandfather, which she recovered in 2015 when she visited her boarded-up family house in Beirut for the first time since the war.

-

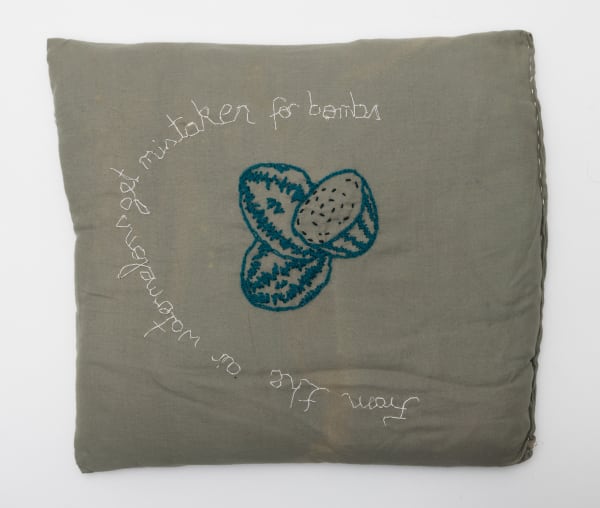

There are a series of cushions with warnings — From the air watermelons get mistaken for bombs — cautionary tales of loaded vehicles as war targets. Language is important to Haidar, as a form and medium she inhabits. She delights in the absurdity of translating from colloquial Arabic such as with her Tolteesh series (2019) where she reappropriates catcalls on intricately designed fabric:

What’s up, custard apple? (A luscious fruit almost exclusively associated with women in Lebanon)Your heart is fire and I’m an ashtrayWhen you sunbathe, the sun meltsMay God ruin your home as much as I love youAs ludicrous as these statements may sound, Arabic speakers rarely question their objectified constructions. Using freehand cursive writing in a way that marks the flow of speaking, they reveal deeply embedded gendered codes.

-

Aya HaidarI felt It III , 2024Felted scourers, Sponges, Dishcloths, Embroidery Thread28 x 28 cm

Aya HaidarI felt It III , 2024Felted scourers, Sponges, Dishcloths, Embroidery Thread28 x 28 cm -

Aya HaidarKiass Series , 2018Embroidery on plastic bagVariable Sizes, 14 pcs

Aya HaidarKiass Series , 2018Embroidery on plastic bagVariable Sizes, 14 pcs -

Aya Haidar,

Highly Strung, 2020 -

“When it comes to mundane work, the division of labour isn’t equal,” she says. “Women’s work is never done. You don’t clock off as a mum.”

-

Aya HaidarTorn, 2024Patched fabric on cotton,150 x 150 cm

Aya HaidarTorn, 2024Patched fabric on cotton,150 x 150 cm